Anthropics and the Egyptology Objection

Why research in Egyptology could be relevant to our decision on whether to have children

Population ethics is concerned with the morality of creating people and how to compare populations with different welfare distributions. Previously, I have defended the repugnant conclusion, namely that a sufficiently sizeable population with barely worthwhile lives would be preferable to a small high-welfare population. Some have embraced alternative ethical theories to avoid this aptly-named conclusion. One popular rebuttal is the average view, which holds that we ought to maximize the average quality of life. Another viewpoint is the variable value theory, in which additional lives have diminishing moral value. These alternative views allow us to reject the repugnant conclusion but have other undesirable implications.

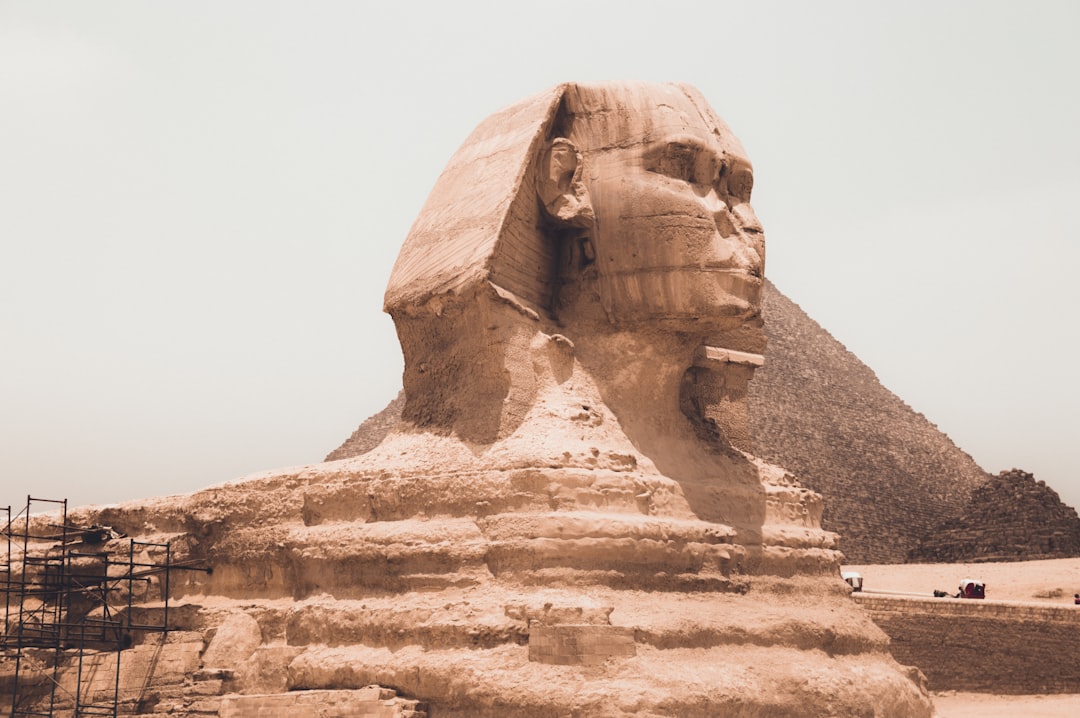

In Reasons and Persons (1984), Derek Parfit countered a version of the average view by highlighting an absurd implication: the ethicality of having children depends on the lives of ancient Egyptians. If they were highly numerous and lived extraordinarily great lives, the average may be higher than previously suspected, so having a child may be unethical. Huemer (2008) argued that this objection could be used against variable value theories. If we learned that the Egyptians were happy and numerous, there would be less reason to produce children in the current year because they would have more diminished moral value. But these scenarios both seem absurd. Parfit states, “research in Egyptology cannot be relevant to our decision whether to have children” (Parfit 1984, p. 420).

Although Parfit’s remark sounds eminently reasonable, it is wrong for extremely non-obvious reasons. Many philosophers have used anthropic arguments to make claims about the universe's conditions, the possibility of a multiverse, the nature of evolution, and the future of humanity. These arguments ask us to consider that we could not be observers if certain conditions that allowed our existence had not been met. These arguments are essential when considering existential risk. An absence of recent extinction-level catastrophes is not reassuring because it is a prerequisite for our existence. Cirković et al. (2010) call this selection effect the “anthropic shadow.”

The lives of ancient Egyptians can be relevant to having children if we adhere to certain anthropic assumptions, most notably the self-sampling assumption (SSA), which holds that “One should reason as if one were a random sample from the set of all observers in one’s reference class” (Bostrom, 2002, p. 66). If we have a reference class of human beings, we should think about our existence as if we could have been any random person across time.

The Egyptian’s lives could be relevant because many adherents of the self-sampling assumption are concerned about an impending doomsday event that would end all human life. If one includes all humans in their reference class, they should expect to be randomly given a position in the birth order. One could expect to be somewhere near the middle of the birth order rather than the far tails. Since the human population is exponentially growing, we would expect a doomsday event soon. Using anthropic reasoning alone, we would expect doomsday a bit later if there were significantly more Egyptians than previously thought. This information may be relevant because one would not want their child to experience a doomsday event or catastrophe that significantly reduces the number of observers.

Even more significant would be if we discovered that many ancient Egyptians spent time considering anthropic selection effects and doomsday scenarios. This would also apply to all previously existing human populations with these thoughts, not just Egyptians. Philosopher Alexey Turchin has argued that an appropriate reference class is those who had considered doomsday arguments of this type, meaning that the start of this reference class was in 1983 when this argument was introduced by Brandon Carter. This would mean we should expect doom exceptionally soon because if we believe we are around the middle of observers who know about doomsday arguments, there are very few people earlier in birth rank, and so there will likely be very few people later in birth rank. But any indication of once-existing human populations discussing doomsday arguments would mean we might have more time because there are more observers before us; thus, we would expect more after us.

Other anthropic assumptions may consider other aspects of ancient Egyptians relevant. For example, Periera (2017) argues for what he calls the Super-Strong Self-Sampling Assumption (SSSSA), which weights the sample depending on the size of the mind in cognitive terms. If the ancient Egyptians were exceptionally intelligent, we might weigh the chance of being an ancient Egyptian more highly in our sampling distribution, lowering the probability of an impending doomsday.

Of course, one could embrace other anthropic assumptions that do not predict doomsday, such as the self-indication assumption (SIA), which holds that “Given the fact that you exist, you should (other things equal) favor hypotheses according to which many observers exist over hypotheses on which few observers exist” (Bostrom, 2002, p. 66). Under this assumption, you should expect to find yourself in worlds with many observers, so you do not need to be concerned about impending doom.

In conclusion, Parfit’s conclusion that “research in Egyptology cannot be relevant to our decision whether to have children” is far too absolute of a statement. Under certain assumptions, facts about distant people and civilizations are relevant to our current civilization and future, and sometimes, they may influence the morality of having children. If one is uncertain, it would be reasonable not to take a firm stance on any particular anthropic assumption. Although tempting, it is unwise to dismiss anthropic reasoning because it is weird. Our existence as seemingly-alone conscious beings in a vast universe is bizarre. Anthropics has many strange and counter-intuitive conclusions, but some could be morally relevant, like an impending doomsday or the existence of extraterrestrial intelligent life. This sort of anthropic moral reasoning should be investigated and discussed more.

You might be interested in an old article of mine offering an alternative to total utility and average utility criteria, a partial ordering of futures with different populations:

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Academic/What%20Does%20Optimum%20Population%20Mean.pdf

So, I am not sure I agree with the sampling assumptions here, but let's run with it for the sake of argument. I have a problem with this statement:

"This information may be relevant because one would not want their child to experience a doomsday event or catastrophe that significantly reduces the number of observers."

I think this is false. Let's consider three cases around it:

1: My child experiences no doomsday, lives to old age, many fat grandkids, etc.

2: My child experiences doomsday, having a decent life before and a bad/non-existent life after.

3: My child has non-existent life (never born).

It seems to me that those three cases are conveniently set in decreasing order of "good". Better to live for a bit then die than never exist, and better to live for a long time then die than never exist.

So, while I am generally negative on the whole "my kids experience doomsday", it is only because it cuts their life time short. Cutting their life time to zero doesn't fix that, and instead makes it worse.

(Note, these cases assume 100% doomsday, and that doomsday is 100% bad. I can't know ahead of time if doomsday even happens, or that my kids won't benefit significantly from it. Who knows, maybe they become warrior queens of the apocalypse and their lives are actually pretty great afterwards? Or, maybe doomsday doesn't happen, like... basically any of the many, many prophesized doomsdays before them.)